March 4th 1863

"...and as I stood alone on the deck after most of the passengers had gone below, I could not help reflecting it was a cruel destiny which had thus compelled us to leave our native land, our friends and homes, to face we knew not what in a foreign land, for if I could have obtained the commonst necessarys of life at home, I would never have emigrated.

To have taken a wife and children away from home and kindred - if man may be excursed for being down hearted and sad it is at a time like this - it was late when I went below and with a heavy heart I went to my bunk."

Extract from the Diary of Abijou Goode

..

"...and as I stood alone on the deck after most of the passengers had gone below, I could not help reflecting it was a cruel destiny which had thus compelled us to leave our native land, our friends and homes, to face we knew not what in a foreign land, for if I could have obtained the commonst necessarys of life at home, I would never have emigrated.

To have taken a wife and children away from home and kindred - if man may be excursed for being down hearted and sad it is at a time like this - it was late when I went below and with a heavy heart I went to my bunk."

Extract from the Diary of Abijou Goode

..

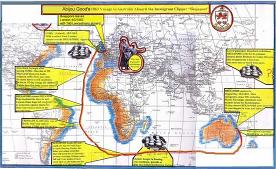

Abijou Goode, his wife Emma and three children left England in March 1863 to emmigrate to Australia.

Extracted from an article by the Sunday Mail, using Abijou Goode's diary as source.

THE words Coventry emigrant Abijou Goode wrote aboard the former tea clipper Beejapore as it was towed down the Thames River on its way to Australia on March 4, 1863, probably summed up the feelings of all the pioneers who helped make the Land Down Under.

Goode was an unusual man. He kept a daily diary of the voyage into the unknown. He and many others had lost their jobs, particularly those in cotton milling as the industry closed down when the American Civil War cut cotton supplies.

On the Thames, Goode was in for a few surprises after boarding Beejapore several days before departure. To his horror he discovered that he, his wife and three children were crammed into a cabin with another family of mum, dad and five kids. The cabin measured 2.75m by 1.83m and was 2.14m high. Step that out in your lounge room and see how you'd cope during a 113 day cruise of the world, including the last 92 days, from Cork to Australia, with no ports of call and during which you would see land just once.

Initially Goode's cabin was dark and dry but almost as soon as Beejapore left the Thames, towed by a powerful steam tug, a howling southwesterly hit the ship, sending water into Goode's cabin through the ventilators and causing most of the passengers to become seasick.

The poor weather continued along the southern coast of England and the smell of vomit rarely left the ship. Twice the powerful hawsers towing the ship broke and Beeiapore was forced to take shelter in English harbours. The captain finally sent the tug back to London and continued on under reefed sail.

Among all this chaos there were good points, for while Goode's cabin was crowded, Beejapore's decks were wide and easily coped with the 240 mostly English passengers. After all, Beejapore had carried 1000 immigrants to Melbourne on a previous trip, so coping with just 240 was a breeze.

Then, after 15 days of mainly terrible weather and huge seas which almost capsized Beejapore, the vessel arrived in Cork Harbour, Ireland.

The English passengers were surprised, having imagined it was a non-stop voyage to Australia, tedious enough without calling into ports along the way.

Two days after anchoring and shortly before Beejapore was scheduled to sail out of the harbour, there was another great surprise: 450 Irish men and women came aboard in great confusion.

Goode did not try to hide his distaste for the Irish intruders. He records some of their ignorant ways in his diary, like the Irishman drinking tea out of the tin chamber pot issued to all passengers on boarding.

Goode's animosity was reciprocated by many of the newcomers and tension was high from the outset. Another passenger, J.T.S. Bird, who was to become a reporter on the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, years later named a Catholic priest as the peace-keeper of the voyage.

Bird wrote: "Though the nationalities were some time in settling down amicably together, Father T. Keating, who was the representative of Bishop Quinn, by his gentle persuasiveness did much to curb the turbulent spirits.

"Protestants and Roman Catholics alike held the gentleman in high esteem and the writer feels certain that to his actions may be attributed much of the peacefulness of the voyage."

Bishop Quirm, of Brisbane, organised a Catholic immigration scheme, similar to a Presbyterian scheme initiated in 1848 by Sydney's the Rev Dr John Dunmore Lang, the object being to dominate the new land with your preferred religion. The Government regulated immigrant numbers; English were to make up seven twelfths of the intake, Irish three-twelfths and Scots two-twelfths.

Things were far from peaceful, however, as Beejapore prepared to leave Cork Harbour for Rockhampton on March 23. An Irishman came on board with a. ticket he said he had bought from an English passenger in a Cork pub the night before.

He also had all the Englishman's personal papers and possessions. He turned out to be an army deserter suspected of murdering the English passenger, and was handed to police.

Two drunken ladies, who had been on the town the night before, turned up and were immediately kicked off the ship with their possessions, by the ship's German doctor. They complained to police and were put back aboard.

As Beejapore was towed down the harbour three wildly waving male passengers appeared on the wharf, now some distance away, but Captain Edward Drenning refused to return. The men hired a rowboat and three oarsmen and set off in pursuit. They made some ground but a strong wind came in, making their pursuit hopeless. The captain relented, stopped the tow and waited for the three men.

As they climbed aboard a woman and child on deck .started screaming. Their missing husband and father was not one of the three latecomers. His papers and ticket were given to the harbour pilot for delivery to the missing husband with the message that he could get the next ship of the line to Australia. The wife and child left for Australia without their breadwinner.

Despite calm weather Goode noted the delicate nature of some of the Irish passengers: "The weather was beautifull but we had not gone many miles before a great deal of sickness began to show itself amonst the Irish. They were lying about the deck in grand stile and we all expected to see some fine sport when the weather became rough."

The first death aboard Beejapore occurred a fortnight after leaving Cork when an Irishman died of tuberculosis. There was so much wailing among his extended family during the burial service that Father Keating had to tell the mourners to be quiet or he would not continue. The mourners were tearful but hushed until the canvas covered body was slipped overboard, where the badly weighted bundle refused to sink and floated close to the ship for some distance while the mourners wailed.

Soon after that first death, the first child, a girl, was born aboard. In all, 36 passengers died, including 32 children. Juvenile deaths were blamed on "fever, typhoid and measles".

When the deaths were reported at journey's end, the Rockhampton newspaper declared: "With regard to the large percentage of children's deaths, we fear no satisfactory explanation can be tendered. In the first place, we think it must be apparent to all that the vessel was far too crowded and in the next it may be justly suspected that there were certain deficiencies (shortage of medical stores and comforts) at the outset of the voyage which have had something to do with the indicated juvenile mortality."

The ship's doctor - "... a more weak minded fool than the dockter has sildom lived", according to Goode's diary received a written death threat less than three weeks into the voyage.

Armed guards were placed outside his cabin. Within days the doctor called a meeting of all passengers, told them he was resigning and would not treat them even if they were dying. But he was back in business a few days later.

Crossing the equator, Captain Drenning refused the traditional "interview" with Neptune but, with the weather extremely hot, had a large sail lowered overboard, allowing all who were able to swim within its protection from sharks.

Goode's diary noted some tension and fights between Irish and English passengers in this extreme equatorial heat. Some sailors and petty officers were also clamped in irons for drunkenness, but there was still almost nightly singing and dancing on deck in good weather.

Beejapore encountered several other homewardbound sailing ships in this area; one, from Adelaide to London, had been becalmed for seven weeks. The only land sighted on the entire voyage from Cork to Fraser Island appeared on April 30, uninhabited Trindade Island, 1100 km east of Brazil. Some weeks later Beejapore was making her run for the prevailing westerlies, the Roaring Forties, more than 600kni south of Cape of Good Hope, there to catch the winds and swing east on the long haul to Australia.

And where passengers had been sweltering just weeks before, they now froze in sleet and ice, some mornings with 10cm of snow covering the deck. It was in this cold and stormy southern latitude that a passenger slipped and fell on to a slack sail which suddenly tightened when it filled and flicked him into the boiling ocean.

A lifeboat was launched in deadly conditions but the man had disappeared.

Beejapore, of 1676 tons, reached an incredible 14 knots before the westerlies and at one stage covered 480km in 24 hours. She sailed well south of Tasmania and it was not until June 21 that passengers saw their new home, Australia, for the first time; Sandy Cape, the northern tip of Fraser Island.

The day had started dramatically with a hatchway lamp bursting into flames, throwing passengers into wild panic before it was brought under control. It was the second such fire on the trip.

But the day ended with a good omen. Goode wrote: "At dusk we could plainly see a cluster of islands called Sandy Cliffs. A little before dark, while lying about 20 miles from land, a beautiful Australian butterfly was cautch on deck."

Four days later, June 25 1.863, Beejapore dropped anchor in Keppel Bay. About 500 passengers were taken by the steam ferry Queensland to Rockhampton, no doubt with high hopes of obtaining the "commonst nessasarys of life" as employers greeted them offering jobs of all descriptions.

On the Beejapore, anchored in Keppel Bay, strong drink was flowing free among the crew and trouble was brewing. It started with a drunken third mate attacking a passenger and ended in mutiny after which 26 sailors and petty officers were clamped in irons and charged.

They were soon convicted and sent by steamer to Brisbane.

Beejapore followed a few days later, and after discharging the remaining passengers and cargo, took the 26 prisoners on board and left for Peru to take on a cargo of seabird-droppings guano before heading home to London. She disappeared without trace.

Abijou Goode accepted a job in the Outback west of Mackay, the journey from Mackay made by bullock wagon and walking. It took them a month to get there, the last days in driving rain.

His diary ends there on a very miserable note written as rain poured through the roof of his family's new quarters, a slab hut with its dirt floor and gaping walls:

"In England a man would be ashamed to put his donkey in sush a place. This then was the home I have traveled some 18,000 miles to find."

Such are the fortunes of a man seeking the commonst necessarys of life.

THE words Coventry emigrant Abijou Goode wrote aboard the former tea clipper Beejapore as it was towed down the Thames River on its way to Australia on March 4, 1863, probably summed up the feelings of all the pioneers who helped make the Land Down Under.

Goode was an unusual man. He kept a daily diary of the voyage into the unknown. He and many others had lost their jobs, particularly those in cotton milling as the industry closed down when the American Civil War cut cotton supplies.

On the Thames, Goode was in for a few surprises after boarding Beejapore several days before departure. To his horror he discovered that he, his wife and three children were crammed into a cabin with another family of mum, dad and five kids. The cabin measured 2.75m by 1.83m and was 2.14m high. Step that out in your lounge room and see how you'd cope during a 113 day cruise of the world, including the last 92 days, from Cork to Australia, with no ports of call and during which you would see land just once.

Initially Goode's cabin was dark and dry but almost as soon as Beejapore left the Thames, towed by a powerful steam tug, a howling southwesterly hit the ship, sending water into Goode's cabin through the ventilators and causing most of the passengers to become seasick.

The poor weather continued along the southern coast of England and the smell of vomit rarely left the ship. Twice the powerful hawsers towing the ship broke and Beeiapore was forced to take shelter in English harbours. The captain finally sent the tug back to London and continued on under reefed sail.

Among all this chaos there were good points, for while Goode's cabin was crowded, Beejapore's decks were wide and easily coped with the 240 mostly English passengers. After all, Beejapore had carried 1000 immigrants to Melbourne on a previous trip, so coping with just 240 was a breeze.

Then, after 15 days of mainly terrible weather and huge seas which almost capsized Beejapore, the vessel arrived in Cork Harbour, Ireland.

The English passengers were surprised, having imagined it was a non-stop voyage to Australia, tedious enough without calling into ports along the way.

Two days after anchoring and shortly before Beejapore was scheduled to sail out of the harbour, there was another great surprise: 450 Irish men and women came aboard in great confusion.

Goode did not try to hide his distaste for the Irish intruders. He records some of their ignorant ways in his diary, like the Irishman drinking tea out of the tin chamber pot issued to all passengers on boarding.

Goode's animosity was reciprocated by many of the newcomers and tension was high from the outset. Another passenger, J.T.S. Bird, who was to become a reporter on the Rockhampton Morning Bulletin, years later named a Catholic priest as the peace-keeper of the voyage.

Bird wrote: "Though the nationalities were some time in settling down amicably together, Father T. Keating, who was the representative of Bishop Quinn, by his gentle persuasiveness did much to curb the turbulent spirits.

"Protestants and Roman Catholics alike held the gentleman in high esteem and the writer feels certain that to his actions may be attributed much of the peacefulness of the voyage."

Bishop Quirm, of Brisbane, organised a Catholic immigration scheme, similar to a Presbyterian scheme initiated in 1848 by Sydney's the Rev Dr John Dunmore Lang, the object being to dominate the new land with your preferred religion. The Government regulated immigrant numbers; English were to make up seven twelfths of the intake, Irish three-twelfths and Scots two-twelfths.

Things were far from peaceful, however, as Beejapore prepared to leave Cork Harbour for Rockhampton on March 23. An Irishman came on board with a. ticket he said he had bought from an English passenger in a Cork pub the night before.

He also had all the Englishman's personal papers and possessions. He turned out to be an army deserter suspected of murdering the English passenger, and was handed to police.

Two drunken ladies, who had been on the town the night before, turned up and were immediately kicked off the ship with their possessions, by the ship's German doctor. They complained to police and were put back aboard.

As Beejapore was towed down the harbour three wildly waving male passengers appeared on the wharf, now some distance away, but Captain Edward Drenning refused to return. The men hired a rowboat and three oarsmen and set off in pursuit. They made some ground but a strong wind came in, making their pursuit hopeless. The captain relented, stopped the tow and waited for the three men.

As they climbed aboard a woman and child on deck .started screaming. Their missing husband and father was not one of the three latecomers. His papers and ticket were given to the harbour pilot for delivery to the missing husband with the message that he could get the next ship of the line to Australia. The wife and child left for Australia without their breadwinner.

Despite calm weather Goode noted the delicate nature of some of the Irish passengers: "The weather was beautifull but we had not gone many miles before a great deal of sickness began to show itself amonst the Irish. They were lying about the deck in grand stile and we all expected to see some fine sport when the weather became rough."

The first death aboard Beejapore occurred a fortnight after leaving Cork when an Irishman died of tuberculosis. There was so much wailing among his extended family during the burial service that Father Keating had to tell the mourners to be quiet or he would not continue. The mourners were tearful but hushed until the canvas covered body was slipped overboard, where the badly weighted bundle refused to sink and floated close to the ship for some distance while the mourners wailed.

Soon after that first death, the first child, a girl, was born aboard. In all, 36 passengers died, including 32 children. Juvenile deaths were blamed on "fever, typhoid and measles".

When the deaths were reported at journey's end, the Rockhampton newspaper declared: "With regard to the large percentage of children's deaths, we fear no satisfactory explanation can be tendered. In the first place, we think it must be apparent to all that the vessel was far too crowded and in the next it may be justly suspected that there were certain deficiencies (shortage of medical stores and comforts) at the outset of the voyage which have had something to do with the indicated juvenile mortality."

The ship's doctor - "... a more weak minded fool than the dockter has sildom lived", according to Goode's diary received a written death threat less than three weeks into the voyage.

Armed guards were placed outside his cabin. Within days the doctor called a meeting of all passengers, told them he was resigning and would not treat them even if they were dying. But he was back in business a few days later.

Crossing the equator, Captain Drenning refused the traditional "interview" with Neptune but, with the weather extremely hot, had a large sail lowered overboard, allowing all who were able to swim within its protection from sharks.

Goode's diary noted some tension and fights between Irish and English passengers in this extreme equatorial heat. Some sailors and petty officers were also clamped in irons for drunkenness, but there was still almost nightly singing and dancing on deck in good weather.

Beejapore encountered several other homewardbound sailing ships in this area; one, from Adelaide to London, had been becalmed for seven weeks. The only land sighted on the entire voyage from Cork to Fraser Island appeared on April 30, uninhabited Trindade Island, 1100 km east of Brazil. Some weeks later Beejapore was making her run for the prevailing westerlies, the Roaring Forties, more than 600kni south of Cape of Good Hope, there to catch the winds and swing east on the long haul to Australia.

And where passengers had been sweltering just weeks before, they now froze in sleet and ice, some mornings with 10cm of snow covering the deck. It was in this cold and stormy southern latitude that a passenger slipped and fell on to a slack sail which suddenly tightened when it filled and flicked him into the boiling ocean.

A lifeboat was launched in deadly conditions but the man had disappeared.

Beejapore, of 1676 tons, reached an incredible 14 knots before the westerlies and at one stage covered 480km in 24 hours. She sailed well south of Tasmania and it was not until June 21 that passengers saw their new home, Australia, for the first time; Sandy Cape, the northern tip of Fraser Island.

The day had started dramatically with a hatchway lamp bursting into flames, throwing passengers into wild panic before it was brought under control. It was the second such fire on the trip.

But the day ended with a good omen. Goode wrote: "At dusk we could plainly see a cluster of islands called Sandy Cliffs. A little before dark, while lying about 20 miles from land, a beautiful Australian butterfly was cautch on deck."

Four days later, June 25 1.863, Beejapore dropped anchor in Keppel Bay. About 500 passengers were taken by the steam ferry Queensland to Rockhampton, no doubt with high hopes of obtaining the "commonst nessasarys of life" as employers greeted them offering jobs of all descriptions.

On the Beejapore, anchored in Keppel Bay, strong drink was flowing free among the crew and trouble was brewing. It started with a drunken third mate attacking a passenger and ended in mutiny after which 26 sailors and petty officers were clamped in irons and charged.

They were soon convicted and sent by steamer to Brisbane.

Beejapore followed a few days later, and after discharging the remaining passengers and cargo, took the 26 prisoners on board and left for Peru to take on a cargo of seabird-droppings guano before heading home to London. She disappeared without trace.

Abijou Goode accepted a job in the Outback west of Mackay, the journey from Mackay made by bullock wagon and walking. It took them a month to get there, the last days in driving rain.

His diary ends there on a very miserable note written as rain poured through the roof of his family's new quarters, a slab hut with its dirt floor and gaping walls:

"In England a man would be ashamed to put his donkey in sush a place. This then was the home I have traveled some 18,000 miles to find."

Such are the fortunes of a man seeking the commonst necessarys of life.

© 2007 Olive McLeod. All rights reserved. This material may not be reproduced, displayed, modified or distributed without the express prior written permission of the copyright holder. For permission, contact olivia@olivemcleod.com

See the complete diary here (pdf -163k)

Terms of Use

Privacy

Home

Abijou Goode

JJ Davis

Milne Family

McLeod Family

AB Milne

AB Milne

Anne Milne

Young Olive

Eimeo

Tom & Olive

Roddy & David

Olive's mob

Friends

Places

Countries

Audio

Sundry

Contact me

Links